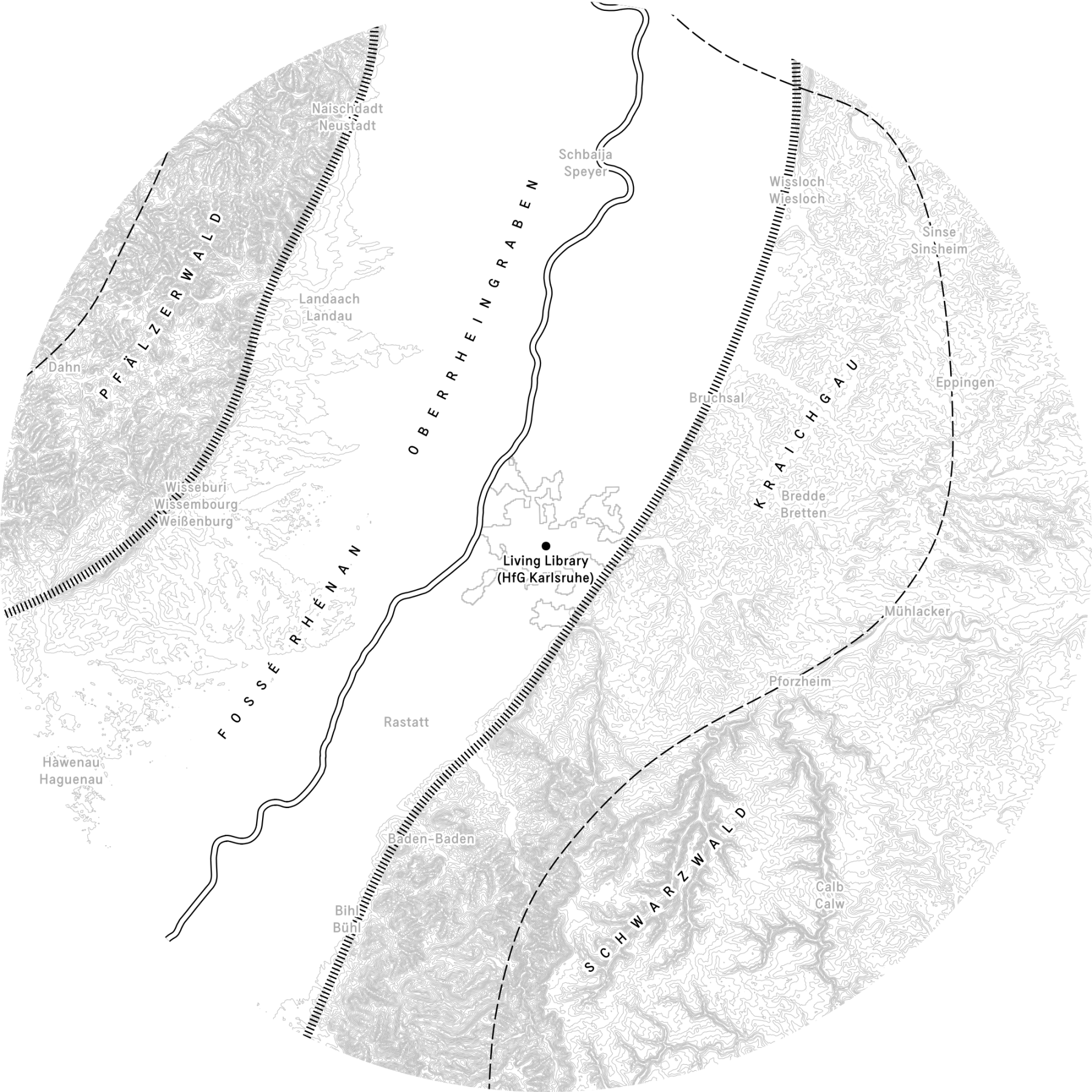

A bioregional map of Karlsruhe

To create a base map or ground map for our local bioregion around the Living Library, I had to question two essential terms: ‘bioregion’ and ‘local’.

What do I consider a bioregion? And what do I consider local?

A bioregion could take on many meanings in different contexts, but for our purposes, I began by thinking of it as an area where “nature and humankind constituted an identifiable ‘community’” (Berg and Dasmann, 1978). In other words, an area with nature and people which contained some kind of ‘border’ which separated it from other areas. As Justinien Tribillon noted in his essay Off the Map, this meant defining an area not by its political borders, but by its natural ones—such as mountain ranges, rivers, and forests (Tribillon, 2024).

Bioregionalist Brandon Letsinger expanded on this by describing bioregions as defined not only by natural borders but also by the people living there. He divided the key components of a bioregion into two categories: ‘scientific’ and ‘cultural’ (Letsinger, 2020). The scientific aspects included unique geological and geographical features, like plate tectonics, erosion, and soil types. Cultural features manifested in language, sports, economic activities, and other human elements.

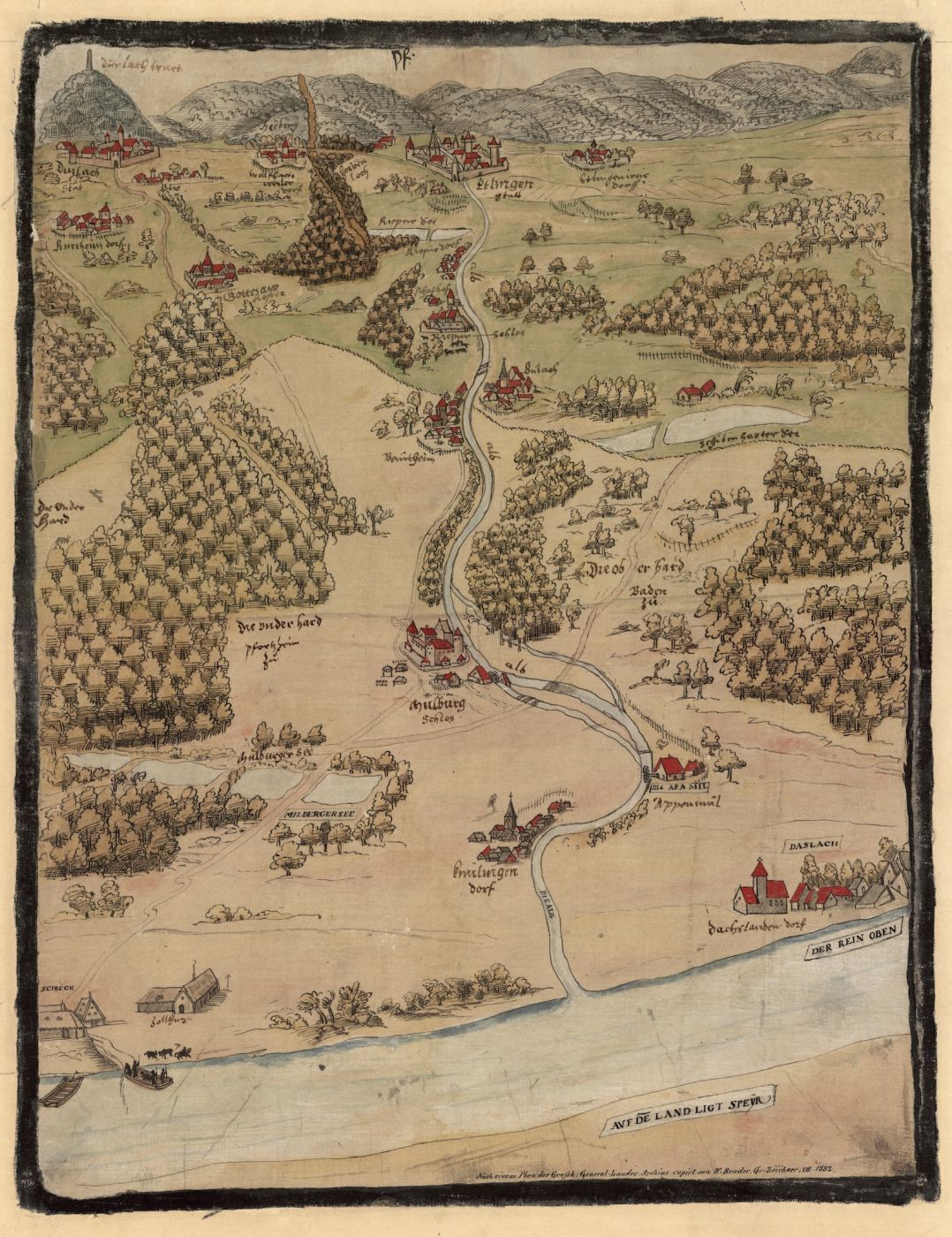

Map of the region around Karlsruhe from the end of the 16th century. Starting from the Rhine river, the map looks east following the river Alb towards the Black Forest. © Stadtarchiv Karlsruhe 8/PBS XVI 1.

The Living Library (and the Bio Design Lab) are housed in a building called ‘Hallenbau A’ (literally translated: ‘Building A’), a former weapons factory dating back to 1922. Hallenbau A is located in the Südweststadt (South-West district) of Karlsruhe.

Taking a bird’s-eye view, one sees that the city of Karlsruhe is surrounded by a broad plain valley through which the river Rhine flows. This valley is called the Oberrheinebene Oberreingraben (Upper Rhine Plain), a rift formed 30–50 million years ago when the European and African continents collided. From Basel in the south downstream to Frankfurt in the north and beyond, the Oberrheinebene stretches 350 kilometres.

The landscape consists of several visually distinct regions, such as the Südliche Weinstraße (a wine region around the city of Landau) and several large forests, including the Hardwald, Bienwald, and Haguenau Forest. But perhaps the most striking feature of this landscape are two large mountain ranges that emerged from fault lines alongside the valley plain. Two curving lines that clearly cut through the landscape, creating natural boundaries on each side.

Fly out further and additional natural features surrounding the Oberrheinebene become visible. To the west, across the fault line, lies the Pfälzerwald (Palatine Forest), an extension of the Vosges mountain range. To the east, the mountains of the Schwarzwald (Black Forest) and the Kraichgau hills.

Two further boundaries that can’t be seen by the naked eye but are nonetheless crucial to nature in the region are formed by the watersheds running along the crests of these same mountains. These hydrological divides—along the Pfälzerwald to the west and the Schwarzwald to the east—created an elongated basin where all water flowed down into the Rhine river. Like the fault lines, the two watersheds form another two lines or boundaries from which I could start to work in my map.

The northern and southern edges of this bioregion (in the making) are less clearly defined using natural features due to the flatness of the Upper Rhine Plain. However, culturally, there are clear indicators of boundaries. For instance, residents of Karlsruhe I talked to often pointed to Mannheim, a city about 60 kilometres north along the Rhine, as definitely ‘outside’ the region because of its distinctive local culture. Similarly, Strasbourg - located across a political border with France - was pointed to as another cultural boundary to the south.

These cultural boundaries—along with the natural fault lines and watersheds—fit neatly within the concept of a bioregion: the Karlsruhe Bioregion.

Jaap Knevel

PS: Why is the map a circle?

In our Living Library Manifesto, we declared that 'everything must be sourced locally'. For the maximum distance we initially chose was 50 kilometres from the HfG Karlsruhe, creating a large circle of 100 km in diameter. For the maps, I chose to re-create this perfect circle literally rather than putting a circle on a square or rectangular map as is the norm.

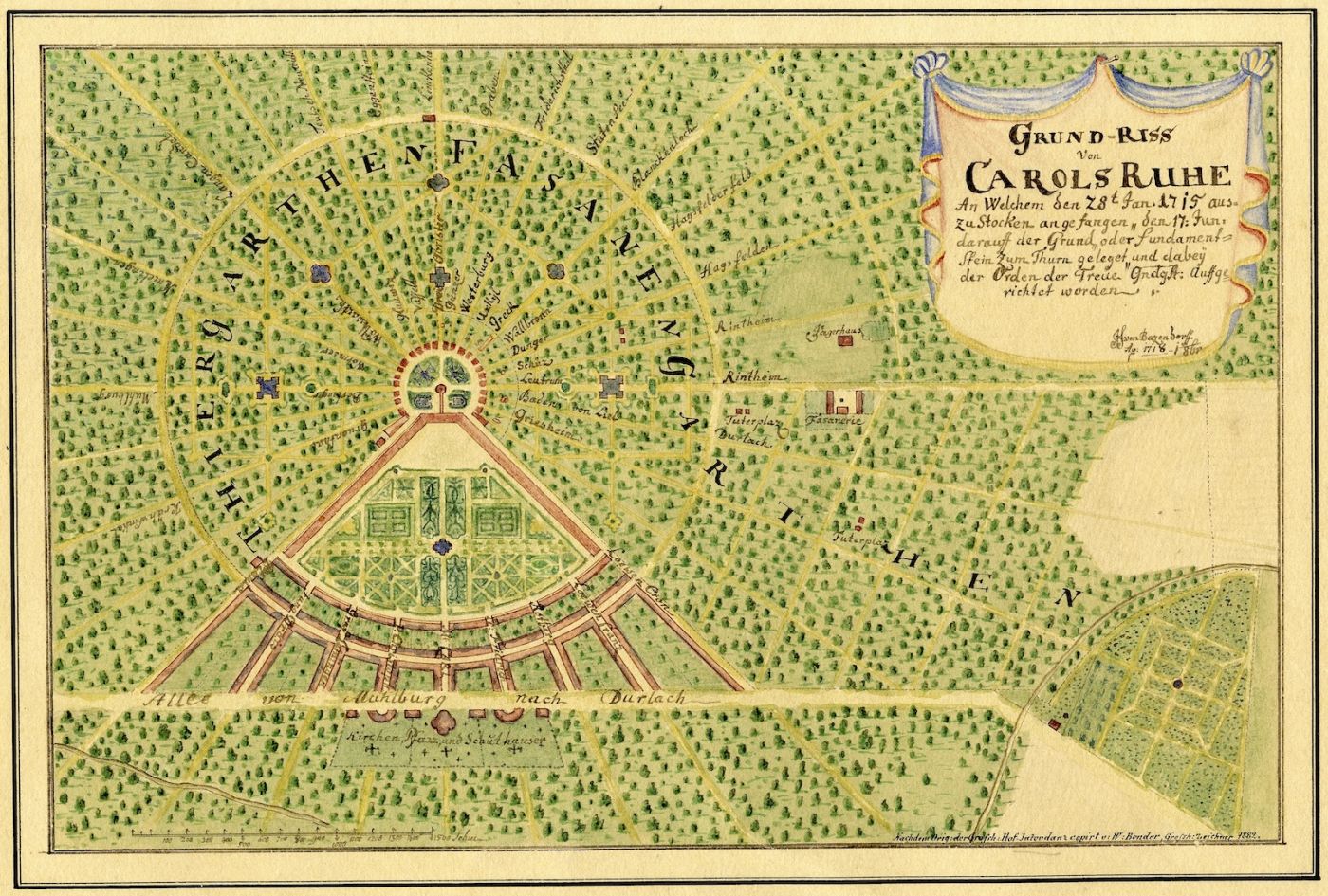

Proposed layout of Karlsruhe from 1718. © Stadtarchiv Karlsruhe 8/PBS XVI 14.

The map as a perfect circle around the HfG is also a reference to the original plan for the city of Karlsruhe, which formed a perfect circle around the Karlsruhe Castle (Schloss Karlsruhe). This circular city plan, with radial streets from the center outwards earned Karlsruhe its nickname 'fan city' (Fächerstadt).

References

- Bio Design Lab (2020) ‘Bio Design Lab HfG Manual’. Staatliche Hochschule für Gestaltung Karlsruhe.

- Ertel, L. and Oberkrome, A.-S. (2020) ‘Atelier LUMA meets ZKM’.

- European Environment Agency (2013) ‘Urban Morphological Zones 2006’. EEA geospatial data catalogue. Available at: https://www.eea.europa.eu/en/datahub/datahubitem-view/24129a43-4bc6-403a-aab8-7f500e69f8be.

- European Environment Agency, European Commission, and Copernicus Land Monitoring Service (2019) ‘CORINE Land Cover 2018’. https://land.copernicus.eu/en/products/corine-land-cover: European Environment Agency. Available at: https://doi.org/10.2909/71C95A07-E296-44FC-B22B-415F42ACFDF0.

- European Space Agency (ESA) and Airbus (2022) ‘Copernicus DEM’. European Space Agency (ESA) (Copernicus DEM). Available at: https://doi.org/10.5270/esa-c5d3d65.

- Joint Research Centre (JRC) and European Commission (2019) ‘LUCAS 2018 TOPSOIL’. https://esdac.jrc.ec.europa.eu/: European Soil Data Centre (ESDAC). Available at: https://esdac.jrc.ec.europa.eu/content/lucas-2018-topsoil-data.

- OpenDEM (no date) ‘OpenDTM-DE’. Available at: www.opendem.info.

- OpenStreetMap contributors (2024) ‘OpenStreetMap’. Available at: https://www.openstreetmap.org.

- Röhr, C. (2023) Der Oberrheingraben. Available at: https://www.oberrheingraben.de.

- Staatliches Museum für Naturkunde Karlsruhe (2018) ‘Geologie am Oberrhein’. Karlsruhe: Staatliches Museum für Naturkunde Karlsruhe.

- Stadtarchiv Karlsruhe and Stadt Karlsruhe (2025) Historische Pläne der Stadt Karlsruhe. Available at: https://stadtgeschichte.karlsruhe.de/materialien-zur-stadtgeschichte/historische-plaene-von-karlsruhe (Accessed: 17 August 2025).